India’s economy has been growing steadily, with impressive figures showcasing its gross domestic product (GDP) performance. However, this growth has not translated into substantial improvements for the poorest segments of society. While the economic elite continues to thrive, demand in the country is weakening, and private investment remains sluggish despite government attempts to encourage it. Protests by farmers, workers, and unemployed youth across different caste and religious groups are growing louder, highlighting the urgent need for reform.

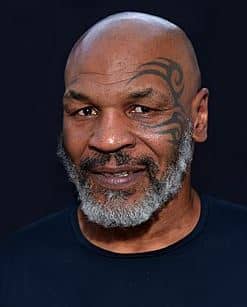

Arun Maira, former member of India’s Planning Commission, argues that while all political parties in India, from Left to Right, agree on the necessity of economic reforms, they are missing the mark. The country’s current economic strategies are not benefiting the poor as they should, leading to rising unrest among the working class. Instead of focusing solely on GDP growth, Maira advocates for policies that prioritize income distribution and better welfare for the marginalized.

Political parties, whether capitalist or socialist, are competing to address these issues. The Right-wing proponents are calling for the completion of the 1991 liberalization agenda, which they argue would increase freedom for capital in land, agriculture, and labor markets. On the other hand, the Left seeks to regulate these markets more effectively to ensure fair wages for workers and proper prices for farmers. However, both sides are resorting to unsustainable solutions, such as direct money transfers (or “revadis”) to citizens to compensate for the market’s failure to provide fair wages and prices.

This reliance on short-term fixes like money transfers, pensions, and food subsidies is criticized by economists who argue that such measures are unsustainable in the long run. Maira asserts that before embarking on further liberal economic reforms, India needs to take a hard look at how well the economy has actually performed since the liberalization of 1991. There is an ongoing debate about whether the reforms of the UPA (United Progressive Alliance) or the NDA (National Democratic Alliance) led to faster employment and income growth. However, this debate, according to Maira, is often clouded by dubious statistics and ideologically driven arguments.

To settle this debate, Maira suggests comparing India’s progress with that of other developing economies that have also undergone economic reforms in the same period. Countries like China and Vietnam, which were similarly poor before the 1980s, embraced economic reforms and foreign trade around the same time as India. Despite these similarities, China and Vietnam have far outperformed India in improving the living standards of their poor. This stark contrast in results calls for a deeper, more objective examination of India’s economic policies.

One key factor contributing to the success of China and Vietnam is that they did not abandon socialist principles, even as they embraced market reforms. While India’s 1991 reforms were based on liberal financial capitalism, China and Vietnam retained aspects of state planning to safeguard the welfare of their citizens. China, under Deng Xiaoping’s leadership, incorporated capitalism into a socialist framework, which allowed it to grow while also prioritizing public welfare. Vietnam followed a similar path, opening its economy while keeping its single-party governance system intact.

By retaining socialist principles, these countries have been able to increase public welfare through state support for key sectors like health, education, and public infrastructure, areas where India’s market-driven approach has often fallen short. In contrast, Russia, which adopted a shock therapy approach to capitalism after the fall of the Soviet Union, faced disastrous consequences. The country’s crony capitalism led to widespread corruption and a steep decline in life expectancy, a stark indicator of the failure of unfettered capitalism in addressing the needs of ordinary people.

Maira contends that India’s economic reformers must pause and reflect on the lessons learned from China and Vietnam, rather than following the purely capitalist model of the West. He criticizes the neoliberal approach for prioritizing GDP growth and the accumulation of wealth at the top, rather than focusing on improving the living standards of the poor. In fact, Maira argues that bad economics, driven by free-market ideologies and corporate lobbies, is corrupting good politics in India. Economic reformers must not remain beholden to outdated theories but should look to socialist countries that have managed to lift millions out of poverty without abandoning public welfare.

After 35 years of economic reforms, Maira points out that Indians in the lower half of the economic pyramid are still struggling to match the living standards of their counterparts in China and Vietnam. Despite starting from similar or worse conditions, these countries have been far more successful in lifting their citizens out of poverty.

The failure to address the needs of the poorest is not just an economic issue—it’s a political one. Maira suggests that instead of focusing on GDP growth, Indian leaders should measure the success of economic policies by their impact on poverty reduction, access to healthcare, education, and social security. Until these core issues are addressed, India’s economic reform agenda will remain incomplete, and good governance will remain elusive.

Ultimately, Maira’s message is clear: India must rethink its economic strategies and look to countries that have balanced market reforms with strong public welfare policies. The focus must shift from the ideals of neoliberal capitalism to a more inclusive economic model that prioritizes the well-being of all citizens, particularly those at the bottom of the economic ladder.